So, continuing with the theme of active investing, I decided to take a look at Pzena Investment Management again. I've been watching it for a while and have posted about it in the past, but the stars are lining up more now than before. I think the sentiment against active investing is at sort of a peak.

I don't usually like investing in themes, though. Those things never seem to work out. Health care stocks because of the aging population, investing in the baby-boom consumption boom, investing in green/environmental, investing in hard assets because they don't make land anymore (versus paper assets) etc. From what I've seen over the years, it just never seems to work out the way people think. Just sticking to great businesses at decent prices seems the way to go.

But sometimes, there are themes that look sort of interesting only because sentiment seems to be leaning too hard one way or the other, and there seems to be interesting investment ideas.

I don't like when things line up

too much in terms of investment themes because that often means a lot of people also agree and it may not work out. But things got more in line this week with the surprise election of Trump. Of course, everyone thought Clinton would win (but she didn't), and many thought that the market would crash if Trump was elected (but it rallied, even though the crash callers were sort of right for a few hours).

This has lead to a huge rally in the stock market with financials finally showing some real strength. Even the Berkshire Hathaway chart looks funny, like it was about to be LBO'ed or something.

Even Stanley Druckenmiller sold his gold and got into stocks on Trump's win. It's true that in terms of trend, DC will probably move away from over-regulation. And banks probably won't have to worry about Sanders/Warren bank-destruction.

Many may not like Trump, but in the end, he has his ego on the line and he is a negotiator so I would not be surprised if he got a lot of things done. Many things people will not agree with, like rolling back environmental/green initiatives. But these can be very pro-business, pro-investment.

So when you see it that way, and see how the industrial cyclicals and banks rallied and the FANGs got killed, if this trend continues, it can really put a dent in the below value cycles charts because the value stocks were the ones that have been suffering in recent years due to this tendency to over-regulate.

Anyway, I usually wouldn't expect a lot of change from an election, but this time the Republicans control congress (Republicans don't really control Trump, though) so there can be a lot more change than usual.

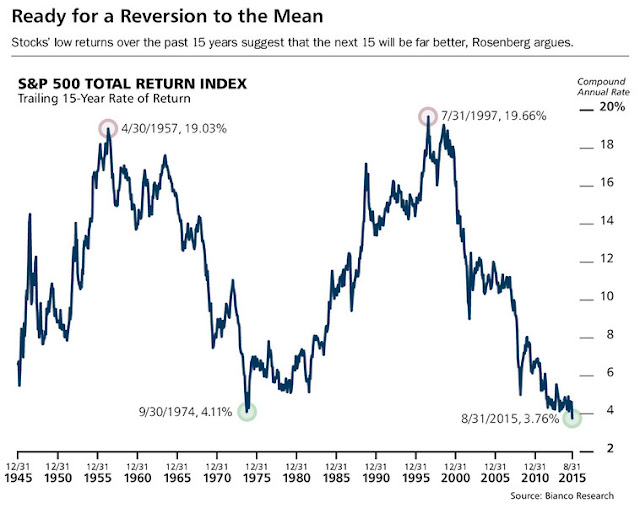

Before we start on PZN, they updated their report on the value cycle so let's look at that. It's really interesting.

Pzena Update on the Value Cycle

Here's the link to their 3Q commentary. Go there and read it:

Pzena 3Q commentary

What really interested me about this idea and why I am so intrigued by it is that for most of the time I've been writing this blog (starting in 2011), people have been saying that the market is way overvalued, that the market will crash, that it's a bubble etc. Even in 2008/2009, people were saying that the sky-high P/E ratios were insane and the market will not recover (even though the high P/E's were due to great recession-depressed earnings).

And each time I read that stuff, I looked at the stocks I own, watch or whatever, and what I saw on my spreadsheets just didn't correspond to what people were saying about the market. I've posted about that over the years. I was always scratching my head.

And then I found these reports and I was like, of course! The market is bifurcated. FANG stocks and many others were going through the roof and had super-high valuations, but many others were just priced normally. Maybe not cheap, but not expensive either. And actually, many were cheap (especially financials).

Anyway, let's take a look at some of the updated charts.

Now that's an amazing chart. Do you want to be long that chart or short it? Some will argue that this looks just like the P/E chart. If you want to short this chart, why wouldn't you want to short the P/E chart too (short stocks). The big difference here is that this chart is a spread between stocks, so it is much more likely for this chart to mean revert than the other P/E chart (which may stay high for years due to lower interest rates; yes, rates are moving up now, but they would have to move up a

lot to get P/E's to revert to 100-year average levels).

If you look carefully at this chart, you will see that the chart mean-reverted as recently as the mid-2000's (actually hitting the lower bound of it, unlike the P/E or CAPE charts).

So this chart is way more likely to mean-revert than raw P/E or CAPE charts. I would

much rather short this chart than a raw P/E or CAPE chart.

And to play this, you obviously want to go long value stocks, or get into a long/short strategies based on valuation (see my previous post about the

Gotham Funds or

OZM).

Pzena shows the same charts/tables for European and Japanese stocks too and it is very interesting. I won't paste those here, though, so go see for yourself.

Check out this table:

This sort of shows the various deep value cycles we've been through over the years. The current cycle hasn't been that great for value, but I see it as sort of an elongated cycle; elongated partly due to the great recession and it's after-effects.

Value Didn't Suddenly Become Useless

I don't think anything happened that suddenly makes value not work anymore. There is a lot of factors at work here, and interestingly, a lot of it may also have to do with the boom in passive investing and the bear market in active investing. People often argue that fundamental stock-picking doesn't work anymore due to indexing and the ETF-ing of the world. But as Buffett said in his 1985 letter, that should really be

great for us value people.

But regulation and subdued economic cycle after the great recession made value stocks perform poorly making active funds not perform well, thus pushing investor capital out of active funds into passive funds thus exacerbating the prolonging of the value cycle etc. This is sort of the self-reinforcing cycle that lead to the extreme valuation dispersion you see in the chart above.

This is not a permanent state, though. We've seen this before.

Anyway, let's take a closer look at Pzena, their funds' performance and how this all ties into the above charts/tables and how it tells an interesting story about the possible future of PZN.

PZN Fund Performance

What's really great about PZN's disclosure is that they have performance figures in their 10-Ks and 10-Qs, with a benchmark. Alternative asset managers usually have this stuff too, making it easier to evaluate as potential investments. Many conventional managers, though, don't show this stuff, so you really have no idea if their funds outperform or not.

I have always been interested in the Affiliated Managers Group (AMG), for example, but that's sort of been my problem. They own fund managers that I really respect, from Tweedy Browne to Yacktman, ValueAct etc., but you really can't tell how they are performing overall. Also, the managers I am familiar with are only a small part of their business. Plus they own a bunch of alternative managers; I would be even more curious about those and how they perform. On a cash earnings basis, AMG is cheap so it is interesting, but that's always been the hurdle for me that I couldn't get over. I don't think they will have a Legg-Mason-(LM)-during-the-crisis type of problem, but that's the thing with alternative managers; if you don't really understand what they are doing, you don't know if there are any time bombs anywhere.

Anyway, let's look at PZN. From the above value cycle charts, we sort of already know that value funds haven't done well in the recent past. You can see that the value spread since the mid-2000's has just continued to widen, meaning expensive stocks got more expensive versus cheap stocks. If you are a value investor, you would be rowing upstream.

The following table is from their 3Q2016 10-Q:

|

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

|

Period Ended September 30, 20161

|

Investment Strategy (Inception Date)

|

|

Since Inception

|

|

5 Years

|

|

3 Years

|

|

1 Year

|

Large Cap Expanded Value (July 2012)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

14.5

|

%

|

|

N/A

|

|

|

9.1

|

%

|

|

14.6

|

%

|

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

14.3

|

%

|

|

N/A

|

|

|

8.9

|

%

|

|

14.4

|

%

|

Russell 1000® Value Index

|

|

13.6

|

%

|

|

N/A

|

|

|

9.7

|

%

|

|

16.2

|

%

|

Large Cap Focused Value (October 2000)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

6.7

|

%

|

|

16.2

|

%

|

|

8.7

|

%

|

|

15.3

|

%

|

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

6.3

|

%

|

|

15.7

|

%

|

|

8.2

|

%

|

|

14.9

|

%

|

Russell 1000® Value Index

|

|

6.3

|

%

|

|

16.2

|

%

|

|

9.7

|

%

|

|

16.2

|

%

|

Global Focused Value (January 2004)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

4.8

|

%

|

|

12.8

|

%

|

|

3.5

|

%

|

|

8.9

|

%

|

|

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

4.0

|

%

|

|

12.1

|

%

|

|

2.9

|

%

|

|

8.2

|

%

|

MSCI® All Country World Index—Net/U.S.$2

|

|

6.2

|

%

|

|

10.6

|

%

|

|

5.2

|

%

|

|

12.0

|

%

|

International (ex-U.S) Expanded Value (November 2008)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

10.3

|

%

|

|

9.7

|

%

|

|

0.5

|

%

|

|

5.9

|

%

|

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

10.0

|

%

|

|

9.4

|

%

|

|

0.2

|

%

|

|

5.5

|

%

|

MSCI® EAFE Index—Net/U.S.$2

|

|

7.2

|

%

|

|

7.4

|

%

|

|

0.5

|

%

|

|

6.5

|

%

|

Focused Value (January 1996)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

10.6

|

%

|

|

17.2

|

%

|

|

9.1

|

%

|

|

16.1

|

%

|

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

9.8

|

%

|

|

16.5

|

%

|

|

8.5

|

%

|

|

15.5

|

%

|

Russell 1000® Value Index

|

|

8.7

|

%

|

|

16.2

|

%

|

|

9.7

|

%

|

|

16.2

|

%

|

Emerging Markets Focused Value (January 2008)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

1.2

|

%

|

|

5.3

|

%

|

|

(1.7

|

)%

|

|

19.8

|

%

|

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

0.3

|

%

|

|

4.6

|

%

|

|

(2.4

|

)%

|

|

18.9

|

%

|

MSCI® Emerging Markets Index—Net/U.S.$2

|

|

(1.2

|

)%

|

|

3.0

|

%

|

|

(0.6

|

)%

|

|

16.8

|

%

|

Global Expanded Value (January 2010)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

7.8

|

%

|

|

12.4

|

%

|

|

4.4

|

%

|

|

9.6

|

%

|

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

7.5

|

%

|

|

12.1

|

%

|

|

4.0

|

%

|

|

9.2

|

%

|

MSCI® World Index—Net/U.S.$2

|

|

8.2

|

%

|

|

11.6

|

%

|

|

5.8

|

%

|

|

11.4

|

%

|

Mid Cap Expanded Value (April 2014)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

6.3

|

%

|

|

N/A

|

|

|

N/A

|

|

|

18.1

|

%

|

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

6.1

|

%

|

|

N/A

|

|

|

N/A

|

|

|

17.8

|

%

|

Russell Mid Cap® Value Index

|

|

6.9

|

%

|

|

N/A

|

|

|

N/A

|

|

|

17.3

|

%

|

Small Cap Focused Value (January 1996)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

13.9

|

%

|

|

20.1

|

%

|

|

10.7

|

%

|

|

18.5

|

%

|

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

12.6

|

%

|

|

18.9

|

%

|

|

9.6

|

%

|

|

17.3

|

%

|

Russell 2000® Value Index

|

|

9.7

|

%

|

|

15.5

|

%

|

|

6.8

|

%

|

|

18.8

|

%

|

European Focused Value (August 2008)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

4.0

|

%

|

|

10.2

|

%

|

|

(1.6

|

)%

|

|

1.9

|

%

|

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

3.6

|

%

|

|

9.8

|

%

|

|

(2.0

|

)%

|

|

1.5

|

%

|

MSCI® Europe Index—Net/U.S.$2

|

|

0.9

|

%

|

|

7.5

|

%

|

|

(0.6

|

)%

|

|

2.5

|

%

|

International (ex-U.S) Focused Value (January 2004)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

5.7

|

%

|

|

10.2

|

%

|

|

0.3

|

%

|

|

6.7

|

%

|

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

4.9

|

%

|

|

9.5

|

%

|

|

(0.3

|

)%

|

|

6.1

|

%

|

MSCI® All Country World ex-U.S. Index—Net/U.S.$2

|

|

5.5

|

%

|

|

6.0

|

%

|

|

0.2

|

%

|

|

9.3

|

%

|

Mid Cap Focused Value (September 1998)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Annualized Gross Returns

|

|

12.8

|

%

|

|

20.0

|

%

|

|

9.4

|

%

|

|

18.3

|

%

|

Annualized Net Returns

|

|

12.0

|

%

|

|

19.2

|

%

|

|

8.7

|

%

|

|

17.6

|

%

|

Russell Mid Cap® Value Index

|

|

10.4

|

%

|

|

17.4

|

%

|

|

10.5

|

%

|

|

17.3

|

%

|

Some of the long term performance is pretty good, but otherwise a mixed bag, but then again, against the backdrop of a 'bad for value' environment for most of the recent past, it may not be so bad. OK, maybe I am being too forgiving. But that's just my view. It has just been a terrible time to be a value investor. The value opportunity chart went from -1 standard deviation to +3 standard deviations. That's a really strong headwind.

Older Record of PZN

OK, so I decided to look further back. How did PZN do when there wasn't such a headwind? From their prospectus in 2007, I found this chart. It's the performance of their value strategy from 1995 to 2007.

Look:

That's really impressive. Great outperformance.

And then go back to the value opportunity chart above. There really was no massive wind at their back in terms of value opportunity. It wasn't like the period 1995-2007 was one where it went from "significant value opportunity" to "limited value opportunity". It looks like, just eyeballing, it went from a period of "limited value opportunity" to "limited value opportunity", but maybe slightly less so. So there wasn't that sort of wind at their back.

But look closer at the above chart. From 1995 to around 2000 or so, PZN was underperforming. And again, go back to the above value opportunity chart, and sure enough, that period of underperformance corresponds to a period when the market went from "limited value opportunity" to "significant value opportunity" in 2000. Bingo!

So this current cycle of underperformance may be a little elongated, but if 1995-2000 is any guide, PZN may have some serious outperformance in store when things mean revert.

And if the period of underperformance is elongated, the period of outperformance may be elongated too. Who knows?

Here's a marked version of the above charts close to each other so you can see it better:

The red arrows show periods bad for value investing and blue arrows show good times for value. We may get a nice extended blue arrow in the next few years. If that happens, that would be great for value funds.

PZN Fundamentals

So what is PZN worth? I don't know. I have no idea. In order to figure that out, you have to know what AUM will be in the future, and I have no idea about that.

But I think if you can make the case that PZN is reasonably valued at current levels of AUM and profitability, then it's a good deal because you are expecting the mean reversion of the above value spread chart and therefore outperformance, maybe even significant and long term outperformance over the next few years. Operating leverage of asset managers here might kick in too as PZN seems to run their funds as a small team (alternative asset managers seem to add AUM by adding teams which doesn't give it the same operating leverage as the cost base goes up).

So that's all I hope to achieve. Let's just see if it's reasonably priced with conservative, reasonable, close-to-status-quo assumptions.

Here are some key data of PZN:

| | | | | Year- |

| | Oper | Oper | DVD/ | end |

| Revenues | income | mgn | share | AUM |

| ($mn) | ($mn) | | | ($bn) |

| 2002 | 32,817 | 15,828 | 48.23% | | 3.1 |

| 2003 | 33,584 | 14,413 | 42.92% | | 5.8 |

| 2004 | 51,896 | 18,050 | 34.78% | | 10.7 |

| 2005 | 78,596 | 31,577 | 40.18% | | 16.8 |

| 2006 | 115,087 | 33,609 | 29.20% | | 27.3 |

| 2007 | 147,149 | 69,378 | 47.15% | $0.11 | 23.6 |

| 2008 | 101,404 | 64,393 | 63.50% | $0.27 | 10.7 |

| 2009 | 63,039 | 29,787 | 47.25% | $0.00 | 14.3 |

| 2010 | 77,525 | 39,970 | 51.56% | $0.24 | 15.6 |

| 2011 | 83,045 | 37,854 | 45.58% | $0.12 | 13.5 |

| 2012 | 76,280 | 37,179 | 48.74% | $0.28 | 17.1 |

| 2013 | 95,769 | 50,848 | 53.09% | $0.25 | 25.0 |

| 2014 | 112,511 | 60,953 | 54.18% | $0.35 | 27.7 |

| 2015 | 116,607 | 55,417 | 47.52% | $0.41 | 26.0 |

You can see that PZN has had a rough history, but mostly due to the financial crisis. If you think something like that is coming soon, then of course, don't bother with this stock. Just wait for the crisis to happen and buy it then.

Otherwise, here are some simple assumptions I made to model their earnings.

First, their AUM at the end of October 2016 was

$27.2 billion. But since the post-Trump rally was good for financials and value stocks in general, and maybe some people will buy PZN funds after reading this post, let's use

$30 billion in AUM. It's not stretch at all from the pre-Trump AUM of $27 billion.

Their average management fee rate was around

0.43% in 2014 and 2015,

0.48% in the past five years, and

0.51% since 2007 (actually this is just revenues divided by average AUM). These figures include incentive fees too, but their inventive fees are nothing like hedge fund/private equity incentive fees so are very small in proportion to management fees.

But still, due to fee pressures across the industry, let's just use

0.4% as the average fee rate.

Also, operating margin has averaged around

50%-51% in the last five years and since 2007. So let's use

50% as the operating margin. Pretax margin has also averaged around 50% since 2002.

OK, and there are around

69 million fully diluted shares outstanding, so let's use that to get operating EPS, or as a proxy for pretax earnings (remember, we like to price things at 10x pretax earnings).

Using the above assumptions, we get to

$0.87/share in operating earnings. There are non-operating items below the operating income line, but I ignored that because that is mostly due to investment gain/losses (which I can't predict and would imagine it wouldn't average out to much over time), and adjustments in tax related things (due to exchanges of units into class A shares etc.) which are non-operational.

10x this $0.87/share figure is around

$8.70/share, not far from where it is trading now.

Non-GAAP EPS in 2014 and 2015 were

$0.51/share and PZN likes to pay 70%-80% of non-GAAP earnings out as dividends. So that would be around

$0.40/share, which is pretty much what they paid out in 2015. And 2015 wasn't even a great year by any means (funds were down).

Anyway,

$0.40/share on a

$8.90 stock price is a

4.5% dividend yield. PZN is trading at

17.4x the

$0.51 2015 EPS, so it is not a screaming bargain, but not terribly expensive either. Asset managers are cheap now, but they used to typically trade at 20x P/E or so.

Operating Leverage

Asset managers are great businesses because if you have a team in place, any increase in AUM due to investment inflows and increase in portfolio value leads to increases in fee income which fall straight to the bottom line (net of some bonuses).

The problem with some of the alternative managers is that sometimes they grow assets by adding new strategies; this requires increasing overhead. Of course, over time, if the new teams can increase AUM, that would be great for earnings.

PZN seems to add strategies more organically. Their expenses have been creeping up lately, but that may just be due to returning expenses to where they were before considerable belt-tightening during and after the financial crisis and there have been additions in sales (increase distribution, mutual funds, London office etc). 2015 operating expenses were higher at $61 million than the $50 million or so back in 2007. First nine months of 2016 is running a little lower than 2015. There were $1.8 million non-recurring expense, though, in 2015.

Conclusion

So even here, PZN is reasonable priced. Not really cheap or anything as is, but the company is positioned well for any recovery in active value investing.

I do believe things are cyclical, especially on Wall Street, and value investing has been in a bear market for a long time. If that rubber band in the above chart snaps back, PZN could be one of the huge winners. They made money through the crisis so PZN is not going to blow up either.